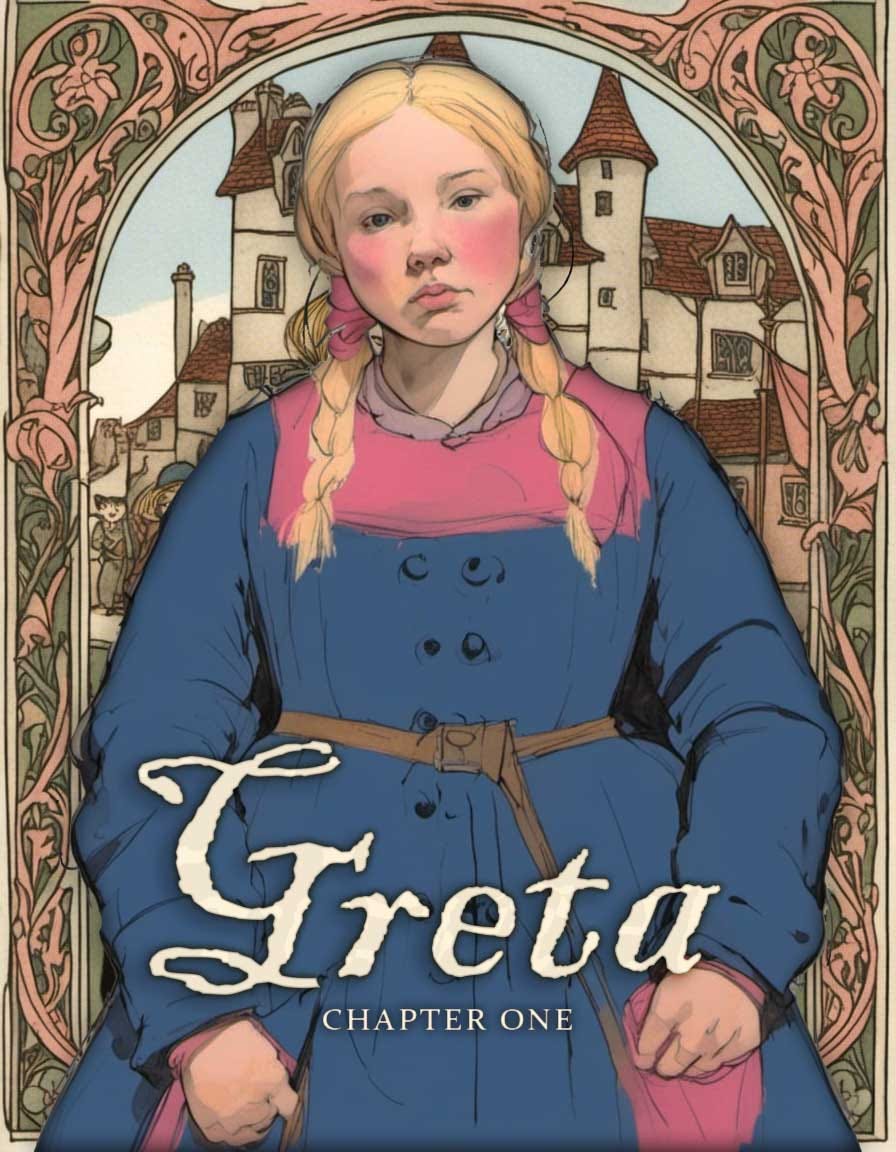

Hans & Greta - A Month of Brambles

My 'sort-of sequel' to 'The Farmer and the Fald'

I’ve been working on a few little pieces the last couple of days, most of them to do with my next journey into the realms of fantasy, going back to the Isle of Rhothodan, there to continue, and conclude, the tale of Hans and Greta as they live through a particularly treacherous Month of Brambles.

Below is the first chapter, “finished” as of yesterday, but very much in its early stages still. Much is likely to change going forward if writing The Farmer and the Fald has taught me anything.

Along with the text and the illustration, I pieced together a (very) rough draft of the opening chapter with a very nifty (not at all frightening) AI filter for my voice. That’s right, it’s MY voice. But all different.

Weird.

There are noticeable hiccups in the track, the conversion messed up the emphasis a few times, and it lost the accents completely, and even inserted a few of its own—along with a few very disconcerting ‘yelps’, screeches and scratchy noises—a glitch, presumably. Either that or the lost souls that fuel the AI mainframe are rejecting their prime directive and beseeching me for aid.

Either way, I got my ‘okay-ish’ narration.

Enjoy!

Chapter I

Greta liked the anvil.

Nothing cheered her mood quite like it.

It was a set of horseshoes today, along with two dozen of the appropriate nails. Master Rufus was heating the iron, ready for its first beating. Greta waited eagerly at the bellows, feeding the forge with a strong, steady breath.

The seasoned smith folded the iron with two and forty strokes, two upon the anvil’s face to flatten it, two around the horn to give it bend, two at the table to smooth the curve and then back to the face, repeated four times, casting it fleetingly back into the fire before finishing the piece with eight divots for the nails, and a deep trench that ran down both branches.

He quenched the iron and set the finished horseshoe with the others, before wiping his brow and handing his hammer to Greta.

Greta didn’t respond, unsure what was expected. Rufus scowled, grabbed the girl’s wrist and planted the hammer in her solid, square grip.

“Go on,” he barked. “Let’s see how sharp your eyes are.”

Hells, she fretted. Greta had never been described as ‘sharp’, in any dimension, and knew so.

That’s what the scythe was for.

But, not wishing to shrink from a challenge, Greta lumbered to the anvil took the pincers from the forge and chose a small billet of iron from the row. It seemed of similar size to her master’s, though to tell the truth, Greta was hardly paying attention. She placed the iron in the forge, as Master Rufus moved to the bellows, and levered a steady heat.

And they waited.

Greta was unaccustomed to feeling nervous. She had avoided death, after all—at the hands of debt collectors, the same that took her father, all those years ago.

Oh—and a dragon, o’course.

She often forgot about that bit. That aspect was all a bit much for Greta, and she had ever been miserly with her thoughts—so why waste them on a dead dragon?

She had taken a life, or two, as well. But, again, she didn’t think much about it.

Needs must, and all that.

“You did what you had to,” that’s what her Mam used to say. "Poor girl, she was forced—driven to it, I daresay. She did what she had to.”

Greta didn’t believe that, though. She didn’t feel forced, or driven—she just did it. It felt like the most natural thing in the world.

He was hurting one o’ the babies. She recalled, her brutish fingers squeezing the hammer’s haft, recalling the weight of the hatchet seven years ago.

And you don’t do that.

The iron hissed in the flames and she withdrew it and, with due haste, put hammer to anvil.

After all that, you gurt lummox, don’t let a gaffin’ horseshoe get the best of ye.

Four and twenty strokes, she remembered. Four and twenty. She struck twice across the anvil’s face to flatten and then took it to the horn for shaping—but the iron wasn’t flat. It was lumpy, and uneven, one blow only glanced the edge. Greta brought the iron back to the face and struck twice more as she silently cursed the knot of nerves tightening in her gut.

But it was still uneven. And what’s more, it had slightly bent when she lay it across the anvil’s horn.

I’ve ruined it. In four strokes I’ve ruined it.

“Keep going,” the old smith barked from the shadows, “a good smith could still save that.”

“But I’m not—”

“You can leave my shop right now If you go sayin’ what I think you’re about to say, missy—hurry now, you’re wasting time.”

Greta bit back her frustration and continued, hope waning with every strike of the hammer. Four and twenty strikes, as Greta was pained to learn, was not enough. After two and forty a curve manifested, but it promptly vanished when she went to refine it. A long time went by, perhaps two of the worst hours of Greta’s whole life, and it was many more than two and forty strokes.

Three hundred sixty-five, one for each day of the year, five feasts and all.

From dance to gaffin’ dirt.

And by the end, sensing her master’s withering patience, she presented her first finished horseshoe. Master Rufus studied it, stroking his thick fingers through his once-red beard, now dark and flecked with gossamer.

“My sister up in high flocks, she owned sorry beast, a grey old mule that had walked the mountain roads for three-and thirty years, ne’er once had he worn a set of proper shoes and ne’er once had he been clipped, and his sorry little hoofs were all wobbly and lopsided and growing over itself—it was a frightful job to clean him up and get him set for shoeing, but hell’s teeth, If only we had your hands at the forge back then—this could be tailored to him, I swear it.”

Greta had known the praise to be false from the start, the old smith bore his look of ridicule, accompanied, as ever, with an over-simpering tone and perpetually raised eyebrows.

Greta looked on, unimpressed.

“Waste of my gaffin’ time,” she spat, throwing the horseshoe to the ground with the resounding clang of iron on stone.

“Don’t bust up good iron, missy,” the old smith warned flatly, walking to the discarded shoe and picking it up in one hand. “You’ve done enough o’ that already. It was an honest jest, not said to wound ye, so stop being so precious. You’re a big girl—biggest I e’er seen.”

He pressed the lopsided horseshoe back into Greta’s, shaky, clammy grip.

“If you hope to improve, you best start acting your size.”

That’s all anyone ever seemed to talk about—her size. But Greta, as her mam often told her, came from a long line of strong and sturdy women, and that it was nothing to be ashamed of. And that had been enough for Greta.

“Sturdy women, burdened by brittle men,” Mam always said, out of earshot of the others. “That's why we grow so big, my girl—‘cause someone bloomin’ has to.”

“If the dragon makes mistakes, his first was setting you in skirts,” Rufus continued. “But then, if he hadn’t, we’d have lost you the crusades, most like.”

Un-gaffin’-likely.

“You put hammer to anvil for two turns o’ the glass, barely a sweat on ya—how’s the shoulder?”

Greta rotated it idly and shrugged.

“Tough as an ox,” he shook his head and sighed. “That’s the hard part done—what you lack is what the noble folk call finesse. And that comes with practice.”

“I’ll get better,” Greta said plainly.

“You will. But only when I have a little more iron spare,” he winked. “See to the two dozen nails, will ya? Two and one-half inches with a thick head—size of a pea. I’ll finish the set; go, water yourself and eat something, your wages are by the door—but back to finish those nails before dusk, leave time to sweep and close shop—remember, the days are getting shorter now we’re into the month o’ Brambles”

Master Rufus drew on the bellows with one hand and set a new piece of iron in the flames.

Greta went to leave, but paused, sidling to her master’s workbench and sheepishly laying the horseshoe amongst a pile of iron scrap.

“Nay! Take that with you,” the smith insisted, never taking his eyes from his forge.

“I don’t want it,” she shrugged and turned to leave.

“Stubborn she-giant, take it,” he barked, casting the shoe at Greta’s feet. “These are instructions, missy, clear and direct, from master to apprentice—you damn well take that thing, and you hang it above your gaffin’ bed. And you look at it, every moment you can spare. It’ll help—you don’t have to understand how. It just will. So do it.”

Greta stooped and picked up the heavy iron, rolling her eyes as she lumbered out of the dark and dusty shop, into the bright midday sunshine, grabbing the pouch by the door and holding it firmly in one hand feeling the meagre weight of the coins.

Should ‘ave enough now, I reckon.

Master Rufus was a decent sort. He wasn’t one to stand on manners and ‘propriety’—whatever that meant—unlike most of the foppish townies Greta had met. He said it how it was, and Greta valued that in a person, more than anything else. He was imperial blood, olive skin and auburn hair gone grey, tall—a few inches taller than Greta—and square across the shoulders, with a big hooked beak and bushy eyebrows. He’d had three apprentices before Greta, but each one had abandoned the forge for the sun and sands of Arencia; joining the ranks of King Doryn’s Third Crusade. It had been seven years since the King died, and his campaign with him, but the lads never came home. Not one.

As a result, Dalkaford—along with every townstead across the isles, most likely—had very few men, and fewer boys. That was Greta’s good fortune, Master Rufus had said so, matter-of-factly, he’d have never taken a girl as an apprentice otherwise, not even one of her size and strength. She might be strong for a woman, but she was decidedly average compared to most of the grown men she’d met.

She scoffed, shielding her eyes from the sun’s rays.

Seen enough sun to last me a lifetime, she mused, donning her wide-brimmed straw hat, the last one her mam made. A tatty thing now, with a few ever-widening holes, and a couple of stray fronds poking up here and there.

Tyr was always good at weaving. Greta mused quietly, tucking the rogue fronds out of sight.

You could always ask her.

But she knew she wouldn’t. It wasn’t in her nature—to ask for things and such.

Besides, their hands are most likely busy with the harvest, I reckon.

It would be pumpkin season at the farmstead, she knew.

Greta missed the farm at times—just occasionally. The smithy was stuffy and sweltering—always, even with the shutters open and the doors ajar. To escape the stifling torment of the shop Greta often sent her thoughts back to those calm days in late summer, when it was just her, her scythe and vast field, ripe and ready for a good sheathing. No floor, no roof, no soot-stained walls, just empty skies and a single, simple task ahead of her.

Greta always valued days like that. She loathed choice, in many ways. Decisions, and the like. They weren’t her forte, by any means.

That’s what Mam was for.

Greta walked beleagueredly into Dalkaford’s square. It was busy today with the sun being out—children playing in the street, dogs indiscreetly humping on the dais, traders, both foreign and domestic, hollering at passersby, and, of course, the odd drunkard shambling about. The usual.

Greta hated the square when it was like this. All…people-y, and whatnot.

Greta sat herself down on the steps of that massive bronze monstrosity, the statue of their late king. The yeolderman had seen it polished and preened in the wake of Good Doryn’s death, scraping off all the gulls’ amassed offerings and layering on a generous layer of wax to protect it from the elements—but the blasted birds had returned, and in greater numbers, for already the statue looked more as she remembered it looking in her youth. Cloaked in white chiton, turning green at the seams and the joins—verdigris, that’s what Master Rufus called it.

Not sure why it needs such a fancy Autrevillian word, Greta thought idly. Surely ‘going green’ works just as good.

Greta disliked Autreville—Autrevillians in general, as a rule.

Foppish, prissy little posers. Don’t trust ‘em, not as far as I could throws ‘em.

Which, in Greta’s case, was a fair bit further than most.

In the shade of the statue of her late king, Greta withdrew her purse, laying it across her lap as she spilt its meagre contents into the bowl of her skirts, taught across both knees.

Three copper, and a couple of small pennies, dinted and dirty—the ones Hans had fished from the well.

It all makes up the weight, Greta mused. No matter how it looks, it’s still copper at the end o' the day.

And then, with as much reverence as Greta was capable, she untied the waxed linen pouch her master had given her and added her new wages to the kitty. Three more copper, new coins, freshly minted, the profile of the young king stamped on one side. They were splendidly shiny—gleaming, pink in the sun.

Greta liked pink. Her Mam always attested that it was ‘her best colour’. Which was fine by Greta, it meant she never had to choose her own.

The perfect copper disks tumbled into her lap, joining the others, seeming to grow dingier in their company.

It all makes up the weight.

She bundled the coins into her purse and journeyed to the Mercer’s office, a little thatched shack built in the northern corner of the square, beneath the stone bell tower. There was already a queue formed. A disgruntled Farmer Digby, labouring under five wicker cages containing perhaps a dozen flustered chickens, each as disgruntled as their master. There were a couple of foreign traders, square-jawed, fair-haired and blue-eyed wearing quartered smocks of red and green atop brown hose and black slippers, their many wares piled high on their backs, secured to packs that rose above their heads half their height again. They were clearly in the early stages of a dispute, throwing foul gestures and guttural curses at each other down the line, jeering and throwing the odd apple core when the other wasn’t looking.

“None of that!” Barked the Mercer from his office, lowering his wired spectacles to throw a withering glare down the line. “Or you can take your goods back to Dubollverk.”

Dubollverk. That’s Gutlund, where Pa was born.

But she thought on it no more than that.

At the end of the queue was a stern-looking mother and a very scrawny, very tearful little boy, clutching a feathered cap sheepishly to his chest. Greta fell in line behind them.

“He might well take a hand for this,” the mother seethed in a hushed tone. “He might flog you in the square like the nasty rotten thief you are. If you were an elf, they’d see you hanged!”

The boy gasped.

“That’s right. Be grateful they don’t string you up, boy.”

The lad sniffled and gormlessly looked over his shoulder at Greta, who stone-faced looked to the mother and raised two fingers, forming a rather vulgar gesture behind her back. The boy’s mouth gaped open.

“What are you gawping at—oh!” The mother turned, and Greta bore neither the reflex nor the inclination to withdraw the gesture in time. It just lingered there, for all to see.

“Did I cause ye some offence?” The mother seethed, thin-lipped.

Greta shrugged.

“That’s all you have to say?” She pursed her lips and folded her arms tight across her chest.

“I didn’t say anything,” Greta shrugged again.

This enflamed the mother’s incredulity no end, and it should be remarked that the gesture was still very much on display.

“You’re from the vale, ain't ye?” She squinted, examining the broad girl inch by inch. “One of them farmers playing at town life—well, things are a wee bit more refined in these parts. You’ll find a touch of civility goes a long way.”

Greta withdrew the gesture.

“Yeah,” Greta agreed idly. She wasn’t completely sure what she was agreeing with, to be honest, but she’d had enough of the confrontation, remembering she had a busy day ahead of her.

“But you were scaring the boy,” Greta referenced the lad with a jerk of her head. “Lines moving, keep your place or I’ll nab it.”

The mother hurried the lad forward, and then, with a laboured tut of disapproval, she turned away and never looked back, being quick to turn the boy’s head forward any time his eyes drifted to the hulking girl behind them.

Greta made another quick gesture and smiled, feeling rather pleased with herself.

Voices were raised and then quieted. Chickens were counted, and coins were divvied about. Disputes were settled, though, far from amicably, and the ratty boy managed to keep both his hands when he confessed to his crime and gifted back the hat.

“Must be the Yeolderman’s. He was convinced it was elves that snatched it,” the Mercer eyed the hat and nodded once he’d determined his claims as fact. “Aye, cormorant feather, milliner’s mark embroidered in the hem—what does it say?—Master Palthos of Kriscany. That be the one.”

“I only snatched it to try it on—but only, sir, when I comes back the wise ol’ yeolderman was gone. Must ‘ave forgotten he had it.”

The Mercer looked unconvinced and silently turned his attention to the mother, muttering a terse: “I trust you’ll discipline the boy,” before dismissing them with an impatient waft of the hand.

His eyes then fell on Greta.

“Oh,” his face fell. “You.”

He wordlessly shuffled from his seat and retrieved from his shack a set of scales and some assorted weights; he set them on his high stool, holding his spectacles to his eyes as he scanned through his big red ledger. When his index finger found the appropriate entry, a snort of laughter came unbidden followed by a withering glare Greta’s way.

“More house cats is it?”

Greta didn’t respond. The Mercer’s eyes followed along the page.

"Three this time. Expanding his business, is he?” He snorted again. “Our Yeolderman has set the fine at seven copper, two per kidnapping—or, perhaps catnapping might be more appropriate—and one to the township for the inconvenience.” The Mercer lifted his eyes from the ledger, set his spectacles down and held out an expectant hand, accompanied by a wry smile, one Greta felt the compulsion to smack off his face.

It’s rarely worth the fuss it causes, mind.

Emboldened by her restraint, Greta, somewhat ungraciously, cast her purse onto the scales, knocking a few of the weights to the floor.

“Don’t!” Proclaimed the Mercer in fright, standing steadfastly between Greta and his wounded scales, lest she strike them unduly again. “Don’t touch,” he warned sternly and ushered her back a pace. “Only I may touch. Step back—go on, go.”

Greta regarded the little man with idle contempt as he darted wary glares her way, taking measure of her coins as he did so.

I think this might be another o’ them ‘brittle men’ Ma told me about.

“You’re one short,” the Mercer concluded. With two fingers he slid the two dinted coins off the table and into his other hand. “I’m not sure what these are meant to be.”

“It’s copper,” Greta gave firmly.

“By your say so? I think not—”

“My Master. He said so. I asked him.” She said with growing impatience.

“Your Master?”

Greta gave no reply, but the Mercer found an answer regardless

“Old Rufus,” he chewed on that a moment, before flicking the coins to Greta and finding his smile again. “Six will suffice, ‘tis hardly an inconvenience.”

Greta made no effort to catch the coins and instead threw a resentful glare the old man’s way for making her bend down, but he was gone before she had time to muster it, which made her all the more resentful as she was forced to keep up, for the Mercer was off, dashing across the cobbles toward the main square, well beyond the reach of her quiet scorn. But she knew where he was heading, so she made no haste—she’d get there in her own time.

The little rat’s been waiting all day, he can wait another five minutes.

Many things were said of Greta’s little brother, but none could claim he didn’t half suit the pillory. He always looked oddly at home there, accustomed as he was to the cramping muscles and the long wait. He chose to make the best of it, as was his way, catching up on some sleep, counting the cobblestones, dislodging any kernels in his teeth.

“It’s a good time to think,” he’d always attest.

“Then you should be better at it by now,” Greta would always say back.

He was alone at the stocks today, save for the half-dozen cats all mewing impatiently at the boy’s heels, mean-looking street cats, with missing eyes and shredded ears, glowering with silent scorn as Greta and the Mercer approached. The cats slunk away, reconvening amongst the jutting joists and gables of the nearby sheriff’s office, watching on like a garrison of grizzled old veterans manning a crumbling tower.

The Mercer eyed the ragged litter with a sneer before turning his ire to the ragged boy they followed.

“Your sister has secured your release,” he said, retrieving the appropriate key from his heavy chain and wrestling it into the lock. “Again,” he punctuated, further emphasised by the rusted clink of the lock’s mechanism.

While pilloried, Hans stood at just under five and a half feet, up high on his tiptoes. Released, he sunk another two inches, stretching and arching his feet on the splintery scaffold in blessed relief, straightening up his spine with a string of clicks and grunts. He had always been small. Not just short, but little with it. ‘Stunted’ was what Greta said if she was feeling mean, that, or runty, ratty, mousy—any rodent fit the bill.

It was easy to be mean to Hans. Too easy—and the townsfolk saw it too.

People threw things at first, Great recalled; spoiled veg and rotten eggs, sodden old bread soaked in sour milk. The townsfolk liked to get imaginative, sometimes. But as her brother’s visits to the stocks grew more and more numerous, the townsfolk took an odd pity on the boy and barely now acknowledged his presence at all, little more than just another pillory.

“This is the part where I, a humble servant of Dalkaford, beseech you to respect the sanctity of the township and see you keep to its laws—but I know that to be a waste of breath.” The Mercer let out a long, tired sigh, and stifled a belch of indigestion. “You have no respect. And what’s more, you’re happy to drag down those around you.”

The Mercer eyed Greta solemnly.

Hans said nothing. He wasn’t even listening, Greta could tell, he had that glassy, clueless look on his face, just waiting for the so-and-so in front of him to finish talking, so he could be on his way.

Hans felt no shame, as far as Greta could tell, and yet he bore an easily bruised pride. One he never dared show in public.

And he recalled all sleights, make no mistake, real or imagined. Ten days past or ten years, he locked it all away behind those steely, grey eyes.

“I trust those cats aren’t the same ones as—” The mercer regarded Hans’s vacant expression, and relented. “—Oh, never mind. I’ll see you within a fortnight, I’m sure.”

The mercer flounced away, rolling his eyes at Greta as he went.

Hans and Greta stood quietly on the scaffold for a moment, a calm breeze blew about them, as the veterans descended their tower, and prowled to their master’s side.

“I ain’t got no food, greedy gaffers,” Hans protested showing the mewing hoard his bare hands. “And If I did, I’d be eating myself.”

“Six copper it cost me to get you out,” Great said plainly.

“Yeah, rubbish that,” Hans mumbled idly, picking a flea from his breeches and crushing it determinedly between his thumb and forefinger. “Since when was befriending a couple o’ gaffing mousers a crime, huh? Swear they just make these laws to squeeze a few more coppers from us.”

“New law?’ Great grunted. “‘Not stealing’ is one o’ the oldest laws there is.”

“But,” Hans puzzled. “Cats?”

“Aye, cats—people spend a lot o’ coin on cats, Master Rufus was telling me. They don’t just appear.”

“They do just appear,” Hans insisted. “There’s more every season. Most of ‘em are this lots little bastards.”

The ragged litter hissed and mewed at their mention, lifting their tails and revealing that, yes, these were indeed six roaming bachelors, temporary allies for this part of the season. No doubt half the scars they carried were caused by their brothers-in-arms.

“And how can someone steal a cat,” Hans continued “I was just nice to ‘em is all, and they followed me home. I suppose I stole their fleas, as well. Or perhaps they stole a few of mine—I should set the price at a copper for each stolen flea, and another for all the upset it’s caused me.”

“But that’s not how it works,” Greta said simply.

“I know it’s not how it works!” He snapped. “I was making a point, weren’t I?—it’s backward, I’m saying. Who comes up with these laws, anyway? Who decides the fines, eh?”

“Yeolderman,” Greta answered, stone-faced. “Or the temple, one or t’other—it’s not you, and that’s what matters.”

“Maybe it should be,” Hans huffed proudly.

“It shouldn’t,” Greta said back. “You’re not a nice person, Hans. Bad at making friends. Very poor judgement. Ma said so, all the time. Up to the end. And, things the way they are, you’re costing me dear.”

Hans didn’t respond to that. Greta had hurt his feelings, she could tell. He turned away when she tried to catch his eye, distracting himself with the affection of his flea-ridden friends.

“Their pity will run dry, one day,” Greta warned him. “I spent my wages today, so if you’re wanting supper, you best find some yourself.”

“Ol’ Roofie always has some ale standing about, he never drains his pitchers. And he won’t miss a wedge or two from of that big smelly wheel o’ cheese he’s so boastful of.”

“That’s stealing,” Greta affirmed. “Stop stealing.”

“Not starving is stealing now,” Hans began, raising his voice as though he were beginning a sermon,

“No,” Greta seethed, trying to quiet the boy. “Stealing is stealing.”

“Pfft,” Hans snorted and turned away. This angered Greta, greatly. She stormed up behind the sullen boy, took hold of his little ratty head and turned it toward the slow bustle of people, as they busied about the streets. Hans wriggled and winced in her grip, as her square fingers found purchase on his scalp.

“Why is it them lot aren’t always strung up on pillories, eh?” She spat. “Them lot, who are all so beneath you. Listen, yer little rat. What’s—what’s wrong with you, eh?”

Greta eased her grip, and her little brother seethed and rubbed his crown to chase away the pain.

“Horrible sausagey fingers,” he muttered under his breath. “You daren’t have called me that while Mam lived—she warned you well away from that name for me, she did.”

“Aye, she did,” Greta gave plainly. “Plenty’d be different if Ma was around. But she’s not. I’ve barely enough wits to keep myself trudging forward, I can’t keep stopping to pick you up.”

“I don’t need picking up,” he sniffed, his pride hurt, his scraggly whiskers wobbling with his chin.

Brittle boy. With a boy’s brittle pride.

Greta stood as stone as her little brother sobbed. He did this now and again, but Greta was never fooled. These tears worked on Mam, always did. But not Greta; not when Hans was four, not when he was twenty, and certainly not now, at four-and-twenty.

Greta never cried, by comparison. She never felt the need and was always rather confused by the custom.

Wasting good water.

And, as though summoned, two of the newly renamed Riverwatch walked on by, eying the brother and sister beneath their conical helms. They wore green now in favour of their old red—as their garrison was now levied by the Temple.

Even now, seven years since Lady DeGrissier and the accursed drought she brought with her, wasting good water was amongst the foulest sins a person could commit on Rhothodan. Though the rationing had ceased over the years, the culture of miserliness left in its wake had lingered long.

“Shouldn’t be loitering at the stocks,” one of the guards warned as they marched on by, chainmail hauberks rattling against greaves and pauldron.

“Rivers that way, if you’re lost,” Hans ‘called’ after them, though quietly enough to ensure they’d never hear him. “Where’s a good hatchet when you need one, eh? Bet you could take ‘em both if you wanted.”

Greta grinned.

“Gaffing right I could,” she ruffled her brother’s thin hair, before grabbing his thin wrist and planting the last of her coppers in his clammy grip. “Whatever you get us for supper, pay for it with this. They’re yours anyway.”

“My coins—did you ask ol’ Roof?”

“They’re copper,” Greta nodded.

“Knew it,” he grinned, showing the gaps in his teeth.

“He don’t like being called that, by the way. He told me to tell you. It has to stop.”

Hans was distracted by his coins.

“Hans,” Greta pushed.

“Yeah—what? I’m listening.”

He wasn’t.

“Oi!” Greta barked. He was listening then. “It has to stop. All of it. It has to. You understand?”

“I understand,” he said, with his usual petulant face, possibly the least reassuring sight she could have seen.

It’s pointless asking. You’ve asked a thousand times already. He don’t hear it—it’s just noise to the boy. Like wind through a valley or crickets in the hedgerows—just empty noise.

Greta saw the low sun, glinting off the slate of the belltower.

“I’m needed at the smithy,” Greta cleared her nose and wiped her hands on her skirts. “I won’t be up till after dark. Stay out of trouble.”

Hans shrugged and turned away.

“Oi,” Greta grunted, grabbing the weasel by his scruff, and turning him back around. “No stealing.”

Hans paled and nodded.

“Don’t waggle at me like a gaffing eel, say it—” Greta shook the boy. “Say it.”

“No stealing,” Hans whimpered.

“Promise,” she shook him again.

“I gaffing promise,” he spat, and Greta placed her little brother back down. He backed away rubbing his pained neck, eying Greta like she was some great she-bear come to devour him.

Greta hated that look. It made her feel half a monster.

“You’re twice the brute you were when Mam was around,” Hans seethed bitterly once he’d taken a few long, safe strides away. “You’d not dare do that if she were around.”

“And you’re thrice the scoundrel,” Greta mumbled. “Imagine her face if she caught wind of yer thieving and yer tricks.”

“It’s not thieving,” Hans wrinkled up his nose. “and they’re not tricks. A man’s not allowed to earn a living, is that it?”

That was always his argument. He had no other, and, what’s more, he knew it, which is why he was now so gingerly walking away from the conversation, his grizzled litter prowling after him.

“Where are you off to?” Greta asked, afraid of the answer.

“I have my duties,” Hans made another petulant face and referenced his cats. “Check the rattraps. Take a couple to feed the lads. Take the rest upstream.”

“Ratcatchers are meant to drown their catches,” Greta said, irritated.

“Aye, the dumb ones,” Hans snorted. “The little gaffers keep me in business, what good is drowning ‘em gonna do me?”

A couple of the townsfolk, the local miller and his wife, overheard the exchange and shot Hans a filthy look. Hans shot a filthier one back.

“Shocked is ye?” He spat at them. “Not so shocked as the town’ll be when they find out you’ve been cutting your flour with chalk.”

“Little rat,” the miller grunted, as he escorted his wife away.

“Does he really chalk his flour?” Greta mumbled, disappointed.

“Probably,” Hans shrugged. “Most of ‘em do, Owyn was telling me.”

“Owyn,” Greta shook her head. “The old farmer always says that skies are rarely as grey as how Owyn sees ‘em…or something of the like.”

“Eh?” Hans wrinkled up his face.

“It don’t matter,” Greta gave sheepishly. “Just be back before dark. And no—”

“No stealing,” Hans called back, his mewing retinue trailing behind. “Promise.”

Greta wished that meant something.

But it don’t.

The realisation lingered, growing stronger as she shuffled through town, back to the smithy, back to the forge.

It don’t mean a damn thing.

I am a fantasy author, illustrator and aspiring poet. If you’d like to help support my projects, you can find my fantasy work here.

My first book ‘The Farmer and the Fald’ is available here.

Also, a big thank you to my faithful three supporters across Patreon and PayPal.